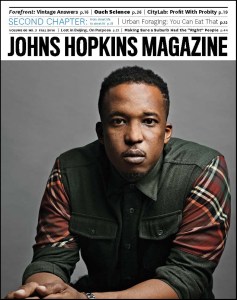

Sequoia Nagamatsu’s forthcoming debut collection, Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone, is a collection of twelve fabulist and genre-bending stories inspired by Japanese folklore, historical events, and pop culture.

Sequoia Nagamatsu is the author of the Japanese folktale and pop-culture inspired story collection, Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Conjunctions, ZYZZYVA, Bat City Review, Fairy Tale Review, and Copper Nickel, among others. He is the managing editor of Psychopomp Magazine and an assistant professor of creative writing at St. Olaf College in Minnesota.

To read Nagamatsu’s story “Placentophagy” and an exercise on defamiliarizing the familiar, click here. In this interview, Nagamatsu discusses first lines, his process for outlining stories, and why realism sometimes falls short.

Michael Noll

The story starts with a solid impact: “My doctor always asked how I would prepare it, the placenta.” I’m curious about the genesis of that line. For some writers, first lines simply appear and the challenge is finding the story that follows, but I know others who start with a scene or an idea and then need to find a line to kick it all off. Was this first line always present in the story?

Sequoia Nagamatsu

For me, I like to do a lot of “writing” in my head long before I actually put any words down. I knew I wanted to write a story about Placentophagy but it took another week or so of thinking about the idea to attach a grieving couple to the practice vs. the story focusing on folk medicine and celebrity mothers who have eaten their placenta (i.e. Alicia Silverstone). Once I had the grieving couple tied to pieces of folklore, I knew I had the necessary emotional tension plus the fun facts that interested me to begin writing.

I believe first lines (and first paragraphs) are crucial to pretty much any story (but especially so for flash pieces where you need to draw the reader in, provide some kind of map of what the story will be about (even if only via tone), and establish character and world building in short order. As an editor, I want a story to provide the central characters, introduce a central tension, and do something unexpected and interesting within the first few lines. Don’t reveal all your cards certainly, but I don’t believe in messing with readers too much. Give them a map of an unfamiliar town. Give the reader something they can navigate as more information is revealed.

As a writer, I don’t continue with a story until I’m satisfied with at least the first few sentences. For this story, the first lines came pretty quickly (with other stories, it can be more of a slog . . . and sometimes I’ll think I have a first line I’m happy with until I finish the story and realize my first line is actually buried somewhere else b/c, as a writer, I was navigating to a destination just askew from where I thought I was going when I started).

This question has made me revisit many of my first lines. A few from my forthcoming collection:

Mayu called me from the train car that Godzilla had grabbed hold of––no screaming or sobbing, no confessions of great regrets, no final professions of love.

Our daughter, Kaede, has returned to us five years after the police fished her out of the community pool, her body sodden and distended like the carcass of a baby seal when I identified her in the morgue.

On our wedding day, you weighed 115 lbs. When you died, you weighed 97. You are now 8.7 cups of ash, and I figure I can make enough 1:25 scale figurines of you from what you’ve left behind, so we can see the world.

Michael Noll

Where We Go When All We Were Is Gone is “an exhilarating debut that serves up every guilty-pleasure pop-culture satisfaction one could hope for while simultaneously reframing and refashioning those familiar low-art joys into something singular, unanticipated, and entirely original,” according to Pinckney Benedict.

Backstory is crucial to the present action in this story, but it’s handled in a quick, compact line: “Somewhere in the building Ayu’s tiny body, caught in the strained expression of her first and last cry, rests in drawer, waiting for someone to fetch her.” Again, I’m curious how much revision was required to achieve such efficiency. Many of your other stories are quite long, which would seem to require a different process than a piece of flash fiction like this.

Sequoia Nagamatsu

When I conceive of a story or a character or a place that I think could contain some kind of world, I start with sketches and summaries. For a longer short story, this might take the form of a rough synopsis. For the novel I’m working on, these sketches might take the form of bulleted points which represent important scenes within an act. I knew from the get go that Placentophagy would most likely be a flash piece, so instead of thinking about my initial sketches as guidelines to be fleshed out later, I made more of a concerted effort to make my notes resemble lines that could potentially be included in the story. The line in question was born from knowing that I needed to capture the loss of a child. Instead of noting “enter scene of miscarriage,” I immediately played around with a couple of variations that captured the essence of this plot point. In other words, when I’m writing smaller and shorter, I inhabit the atoms that make up the molecules of a larger story’s architecture. I need to capture what’s going on at that level.

Michael Noll

I love the essay-ish section about the practice of eating placentas, but I can also imagine workshop readers advocating for it to be cut—because that’s the sort of thing that workshops do. How did you approach that section so that it moved the story forward?

Sequoia Nagamatsu

Whenever I become fascinated with something and consider treating the topic in a story, I tend to be cautious because there’s a real danger that I might dilute forward motion and character with unnecessary minutiae. With that said, I don’t think there is anything inherently wrong with tracts of reportage and “essay-ish” writing in fiction so long as 1) the conventions of the story have been firmly established to allow for such asides (esp. if they are lengthy and a bit more detached from character) and/ or 2) the momentum for characters and the overall story are not completely lost or forgotten. For this section, considering the length of the piece, I knew I would have to pick and choose a couple of interesting facts, tie them to the emotional tension of my narrator, and quickly move on. The facts in this story, while certainly stepping outside of my main character, illuminate her research, as well as her relationship to her children and to her body, so if I chose, I probably could have added a line or two more without much lost momentum.

Michael Noll

When I first read this story, it seemed like a piece of horror fiction. Then, I read some of your other work, which involves science fiction situations and characters, and it all seemed to cohere as a single vision. Horror and sci-fi are obviously different genres, but both depend, to some extent, on defamiliarizing the familiar. Is that what attracts you to these types of stories?

Sequoia Nagamatsu

Defamiliarizing the familiar is something present in pretty much all fiction. But to the degree of horror and fantasy and sci-fi (and its genre-bending cousins by various names: magical realism, slipstream, fabulism), the defamiliarizing is often illuminating aspects of reality whether that be racism or rampant consumerism via what many might consider obviously unrealistic, surreal, or fantastic.

I’ve long been a fan of literature and film that forces me to suspend my disbelief, that takes me to other worlds. I love these kinds of stories because I find them entertaining and imaginative. I love these stories because the primal part of me wants to be afraid, wants to use that fear. I love these kinds of stories because they force me to consider the gadgets around me and how they factor into who I am and who I’ll be 10, 20, 50 or more years from now. To quote the title of a Chan-Wook Park film (of Oldboy notoriety): I’m a cyborg, but that’s okay.

These kinds of stories are important and increasingly necessary because we live in complex times and sometimes “realism” falls far short of what we need to comprehend how fast we are evolving, how we process information, and how we define personal, cultural, and geographic borders and spaces. What we consider fantastical fiction used to simply fall in the realm of story or religion. Our stone age ancestors needed a way to understand and process the world around them. For countries who have had to deal with colonial and post-war transitions, the fantastical has become a vehicle where the distant native past and the unhinged identities of the present intermingle. Today we’re compounding these past relationships born from colonialism and warfare with globalization and technology.

Many of my stories are set in Japan. And for me, Japan is a unique case b/c it is a country that has had to reinvent itself multiple times over a short amount of time (notably in the 1800s when there was a push to westernize and again after WWII when the country shifted from military empire to technological and commercial super power). These shifts occurred so rapidly that Japanese culture & identity couldn’t keep pace, and you’ll note that creatures of Japanese folklore often share the stage with technology or modern society gone awry in anime, showcasing the tenuous relationship between the past and present. Akira was released nearly thirty years ago but has never been more relevant for Japan and the rest of the world.

In short, I’m drawn to and write in the realm of the fantastic because, for me, they are the stories that help me navigate the many spheres constituting who we are.

First published July 2015