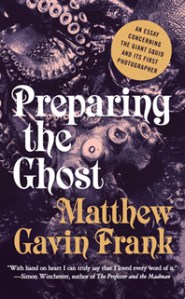

Matthew Gavin Frank’s new book, Preparing the Ghost: An Essay Concerning the Giant Squid and Its First Photographer, contains “stunning writing and perversely wonderful research,” according to a New York Times review.

Matthew Gavin Frank left home at age seventeen to travel and work in the restaurant industry. He ran a tiny breakfast joint in Juneau, Alaska, worked the Barolo wine harvest in Italy’s Piedmont, sautéed hog snapper hung-over in Key West, designed multiple degustation menus for Julia Roberts’s private parties in Taos, New Mexico, served as a sommelier for Chefs Rick Tramonto and Gale Gand in Chicago, and assisted Chef Charlie Trotter with his Green Kitchen cooking demonstration at the Slow Food Nation 2008 event in San Francisco. He received his MFA in Poetry and Creative Nonfiction from Arizona State University. He taught creative writing to undergraduates in Phoenix, Arizona, and poetry to soldiers and their families near Fort Drum in upstate New York on the Canadian border.

Frank is the author of two food memoirs: Barolo, a food memoir based on his illegal work in the Italian wine industry, and Pot Farm, about his time working on a medical marijuana farm in Northern California. He’s also written three poetry collections: “The Morrow Plots,” “Sagittarius Agitprop,” and “Warranty in Zulu.” His most recent book is Preparing the Ghost: An Essay Concerning the Giant Squid and Its First Photographer.

In this interview, Frank discusses the unpredictable rabbit holes of research, the line between fact and conjecture, and getting lost in sentences.

To read an excerpt from Preparing the Ghost and an exercise on creating space for digression, click here.

Michael Noll

I’m really taken with the line, “The fog that the early sailors believed to be the last remnants of Noah’s flood began to shroud the vessel.” Beyond the lovely effect of the imagery, I’m curious about the research involved in such a line. How does one come across a piece of information like this (that sailors once believed the fog to the last remnant of the Flood)? What is your research method like? It would seem to be pretty far-reaching and not necessarily specifically focused on giant squid.

Matthew Gavin Frank

My research process, like my writing process, was digressive. Squid led to ice cream which lead to cold weather which led to hot weather which led to ocean which led back to squid. And so on. I read plenty of late 19th century fisherman’s accounts and articles about the fishing industry in Newfoundland. The fishermen of that time would also trap auks—those fat unwieldy beautiful seabirds—driving them aboard the ships, caving in their skulls with clubs, salting and drying their breasts, feasting on their eggs, selling their bones to the superstitious and the spiritual, stuffing coats with their feathers, burning their bodies for fuel. Reverend Moses Harvey, who plays a great role in Preparing the Ghost (he was the one who first photographed the giant squid in 1874, rescuing it from the realm of mythology, and finally proving its existence) felt that, “It is not wonderful that, under such circumstances, the great auk has been completely exterminated.”

In scholar Weldon Thornton’s annotated Allusions in Ulysses, the author wonders if, in regards to the source text’s line, Auk’s egg, prize of their fray, the auk indeed “has any special mythological or symbolic meaning” or if its usage is “to represent something exceedingly rare.” The 11th edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica provides a soft, wishy-washy answer of sorts, declaring, “A special interest attaches to the great auk (Alca impennis), owing to its recent extinction, and the value of its eggs to collectors.”

So, this is what I mean. Case in point. One thing leads to another, and it’s this lovely cascade down the rabbit hole of research. What fun! When I’m sifting through a roomful of research, I’m seeking out that “exceedingly rare” thing, and I’m interested in seeing what happens when we hold it up against a more known thing. I’m interested in seeing where such a collision will lead. Oftentimes, the most interesting thing we can do as essayists is draw a chalk outline around our main subject in order to suggest its shape; in order to evoke its essence. This ancillary engagement is often more powerful than a direct engagement, as it reveals to us (during the seemingly wayward research process) the specific and intricate blend of chalk necessary to evoke the body.

Yet again, I digress. Anyhow, these early accounts of fishermen [sailing into the St. John’s Narrows] were oddly rife with biblical allusions—I mean the giant squid was known as the Devil-fish before it was known as the giant squid. So the Noah’s flood reference seemed a natural extension of such documented accounts.

Michael Noll

I’m curious about your use of the first person point of view in this excerpt and in the book in general. The excerpt at The Nervous Breakdown is about Moses Harvey in a particular spot on the Newfoundland coast in 1874, and yet you include this line:

I envision Harvey wiping his nose with his right hand, his left never leaving the squid’s body which had a “total number of suckers…estimated at eleven hundred,” and “a strong, horny beak, shaped precisely like that of a parrot, and in size larger than a man’s clenched fist.”

I can easily imagine an editor trying to cut that I—obviously, you weren’t there, and, and, in a way, it’s probably extraneous. And yet it also seems essential. Without it, the detail about Harvey wiping his nose would be out-of-place conjecture. Did you ever struggle with when and how to use the first person point of view?

Matthew Gavin Frank

Oh, yes. It’s always a struggle for me—a holy one—trying to determine to what degree I should signal to a reader that I’m speculating, that I’m imagining, that I’m caught up. Usually, my initial instincts are that I should not overtly signal at all. That context will do its job; that a reader will figure it out. And if it’s muddy in the book—this blurry line between fact and conjecture—that’s because it’s actually muddy. Supposedly factual historical research yields varying—and often conflicting—narratives. Once we impose narrative(s) onto a fact, it ceases to be a hard fact. It softens. It’s shapeable. Like boiling water into which we dissolve sugar teaspoonful-by-teaspoonful, it doesn’t become another thing completely. Until we add that ultimate spoonful which supersaturates the solution, it’s still water, still maintains the integrity of water. It’s still maintains the shape of the original fact. It’s just sweeter.

Throughout the book, there’s this overlap between the contemporary and the historical, our time and Harvey’s. The intrusion of the I sometimes forces this overlapping. It’s funny that you think an editor would be tempted to cut this I. In fact, my editor wanted me to add more of this kind of signaling to the draft I originally submitted, so that the reader felt a bit more tethered; could more easily distinguish between “fact” and speculation on said fact.

Michael Noll

Preparing the Ghost is Matthew Gavin Frank’s third book of nonfiction and has been called, by Matt Bell, “a triumph of obsession.”

There are two sentences in this excerpt about Harvey sailing into the harbor at St. John’s that contain pretty noticeable digressions. The first sentence lists various sites around the harbor, beliefs about those places (“Deadman’s Pond, rumored to be bottomless), and some notable historical events that took place there. The other sentence zooms in on a girl cleaning fish. There’s definitely a more-is-more attitude in these sentences, both in terms of detail and grammar. You can’t really read them once through. I found myself stopping, rereading a phrase or word—but this was not an unpleasant experience, simply a different way of reading. How do you approach passages like these? Do you simply write them when so moved, or is there some underlying strategy at work?

Matthew Gavin Frank

Years ago, I took a class from the fiction writer, Paul Friedman, the gist of which was entirely devoted to the notion of the sentence—its parameters and pitfalls, its strong tightropes and its weak ones. The sentence, in this course, was something to navigate, traverse; something that required the strapping of the essential gear onto one’s body. Ropes. Cleats. Hooks. As my father-in-law would say: the whole toot. I love getting lost in the middle of a sentence— both as writer and as reader, and then having to bust my metaphorical flashlight out of my metaphorical fanny-pack in order to illuminate my way to its end. And then, of course, to re-write it a thousand times. I’d like to say that I wrote this passage in order to empathize with Moses Harvey’s assured ecstasy at approaching the port of St. John’s, Newfoundland in 1874, shell-shocked and bemused beneath the suspended and snotty chandelier of the first intact specimen of the giant squid. But the truth is probably that I was rendering my own ecstasy in the face of all of this wonderful research I uncovered. I fall in love with the objects of my research sometimes, and then all of the tightropes snap, and I’m falling, or rising, or just plain airborne, grabbing at all of the beautiful tinsel-y shrapnel floating past, trying to stitch it all into something that resembles a navigable sentence.

Michael Noll

You’re a writer of astoundingly varied experiences and interests, though they do seem to center on food and consumption. You’ve written books about working in the Italian wine industry and at a medical marijuana farm in northern California. So, a book about the man who first photographed the giant squid seems like a bit of a curveball. What drives your writing? I’d hazard to guess that you have no shortage of things to write about. What makes you choose one over another—and then spend the time necessary to write a book about it?

Matthew Gavin Frank

It’s funny. In trying to shun food writing for a while, I find myself working on a new project that’s attempting to interrogate not only our relationship with food (within regional context), but also our expectations of food writing. Food is complicated. The new book-in-progress is tentatively titled The Food You Require is Heavier: 50 States, 50 Essays, 50 Recipes. At the risk of sounding totally overblown, I’m trying to cobble together this spastic, lyrical anti-cookbook cookbook of sorts that also may be a fun and digressive revisionist take on U.S. history. I’m trying to concentrate on the small events—incantatory and ponderous and horrific and mundane— that we glossed over when we originally (and then subsequently) attempted to set down regional definitions. Each essay begins with this line of questioning: What does Illinois mean? What does deep-dish pizza mean? What ancillary subjects will I have to engage in order to stalk both food and state toward the blurry answers to these questions? The Rhode Island essay, for example, is concerned with Clear Clam Chowder and the Cognitive Psychology of Transparency—how we think and react differently to things we can look through rather than look at. The Louisiana essay deals with the intersection of Crawfish Etouffee, bad weather, and autoerotic asphyxiation.

Being a little OCD helps to dictate my projects and focus for a while as well. I mean, when, during my research process, I found out that squid ink is immortal—invulnerable to decay—and that in the South of England in the 19th century, the petrified remains of a 150-million-year-old squid were discovered entombed in solid rock, and that its own, perfectly intact ink was used to draw a picture of its remains, and that scientists called the resulting image, “the ultimate self-portrait,” how couldn’t I be seduced to catalogue the onrush on implications? I’m easily seduced, is what I’m saying. Immortal cephalopod melanin is all it takes, and I’m yours for a while.

July 2014

Michael Noll is the Editor of Read to Write Stories.