Benjamin Rosenbaum’s story “Feature Development for Social Media” was published at Tor.com. You can find a complete list of his stories here.

Benjamin Rosenbaum is the author of The Ant King and Other Stories. His stories have been published in Nature, Harper’s, F&SF, Asimov’s, McSweeney’s, and Strange Horizons, translated into 23 languages, and nominated for Hugo, Nebula, BSFA, Locus, World Fantasy, and Sturgeon Awards. He lives near Basel, Switzerland.

In this interview, Rosenbaum discusses social media in fiction, our ability to grow accustomed to anything (even zombies), the phrase first world problems, and a tabletop roleplaying game about teenage monsters.

(To read Rosenbaum’s story “Feature Development for Social Networking” and an exercise on story tone, click here.)

Michael Noll

I’ve been struck by the absence of social media in new stories and novels. In fact, the only social-media story I can think of is Jennifer Egan’s “Black Box,” which was written as a series of tweets. So, I love the sections of your story that are written as Facebook messages. What were the challenges you faced in using this form? Was it tempting to treat the medium ironically—to exaggerate or spoof the way people communicate via Facebook. Even though the scenario is far-fetched (zombie attack), the way the characters communicate seems authentic and real.

Benjamin Rosenbaum

I feel like there’s a certain amount of use of social media, instant messaging, etc, particularly in YA fiction. M.T. Anderson’s brilliant novel Feed comes to mind (not written exactly in an epistolary style, but in which the equivalent of IM’ing and tweeting is heavily foregrounded and substitutes for much of the dialogue), or Lauren Myracle’s ttyl.

Interestingly, the direction of my revisions was to tone down the realism of the Facebook usage. It’s not so much that I was tempted to exaggerate and spoof, as that my initial draft was very closely emulating real Facebook usage — for instance, the fact that the responses to a comment do not follow the comment immediately, but occur after a certain lag time during which other comments have intervened. In revision I simplified and threw away some of the peculiarities that are part of real Facebook interactions, but which weren’t thematically central and which made it harder to read smoothly as fiction.

I tried to be pretty naturalistic, rather than broad, because I thought the humor would mostly come from the contrast of the realistic, everyday style of discourse and the fantastical situation. I was going to say “familiar style of discourse” and “unfamiliar, dramatic situation”, but of course it’s really two familiarities — the everyday, real-world familiarity of social networking and the pop-culture familiarity of the zombie outbreak.

If anything, in revision, I made the satire sharper and the characters more distinct. Jewell got bubblier and more committed to lower-case abbreviations, Buster more self-serving and insensitive, etc. In that sense it actually became less naturalistic — the characters moved closer to being types, the way Dickens’s or Austen’s minor characters are. There’s always a balance to be struck between naturalistic and stylized.

Michael Noll

The actual zombie action takes place off the page, referenced but never seen directly. Even when the story’s characters see zombies, they don’t describe them with great detail. In a way, this seems to cut across the zombie genre, which almost always shows gore and carnage eventually. For instance, in this exchange between Facebook employees, one of them writes: “Suresh, you should check out the 2nd floor webcam. There’s not a lot of Grief and Loss Counseling going on up there right now. Nor do I recommend a massage.” I love that this detail is delivered as a literal P.S. to an email about the feature development from the story’s title. This particular exchange ends with one character writing, “Let’s not get distracted people!” On one hand, this is funny. On the other hand, it seems like it keeps the zombie-biting-people stuff from taking over the story. Were plot details like this one always dropped into the story so casually? Did they ever occupy a more direct space?

Benjamin Rosenbaum

So partly, I was going for a humorous deflation of the zombie story. If I’m juxtaposing the mundane detail of the everyday with the horrific detail of the apocalypse, and they are described with equal focus, the horrific details are going to take over emotionally.

Blood and gore are sensational: they force the reader to pay attention, demand an emotional reaction. On the other hand, if you demand an emotional reaction when you haven’t really earned one — when the reader isn’t sufficiently invested in the characters and the action — you get sentimentalism or melodrama rather than a real emotional response. The reader pulls back, because you’re rubbing their face into extreme stimuli without having won them over.

So in a way, distancing the carnage is a double win: primarily, it’s funnier, because it allows the juxtaposition of mundane and extreme to be a balanced juxtaposition. But also, I think it may actually be scarier too, because the little details of what’s going on sort of slip in to the narrative. Something that’s just offstage is often scarier than something in the center of the screen. The end of the movie Blair Witch Project is far scarier than most horror movies where there’s an onscreen monster, because so much is implied, evoked in your imagination. However good the CGI or the rubber suit is, it’s never going to be as frightening as what your brain can project into the unknown. Kelly Link is an absolute master of this; I think “The Specialist’s Hat” is an exquisitely scary story, for instance, precisely because of what we don’t know.

In writing this, funny was more important to me than scary, but the little bit of scary helps bring the funny into relief, and makes it sharper.

There’s another related thing going on here, too, which is that I wanted to talk about habituation, which I think of as one of the most powerful mechanisms of the human mind. It’s like we can get used to anything. Like, in the first decades of aviation, flying was this incredible, awesome, unbelievably thrilling achievement. Human beings could fly — like birds! We had conquered gravity! To ascend to the heavens in a plane was mindblowing, it was this rush of absolute wonder and power. Now we get on a plane and we’re like, security sucks, my seat is uncomfortable, why do I have to put my tray table up, damnit my laptop battery is down and the inflight magazine is boring, what do they expect me to do, spend my time looking out at the clouds? This is actually hilarious when you think about it. And at the same time, people in horrific situations habituate to them too. I just re-read the Diary of Anne Frank, the new edition where they restored a bunch of stuff that had been cut out for propriety’s sake in the 50s. Anne Frank spends very little time on the Nazis. She occasionally remarks that it sucks that they have to hide, and that she’s worried about her schoolmates who didn’t hide in time, and that they’re following the progress of the war. But 90% of the time she’s pissed off at her mother, and at Peter’s mother, and at the guy she has to share a room with. Somebody’s not peeling enough potatoes and someone else is hogging the radio. That’s what life is composed of, whether you are an internet billionaire or a hidden Jew in occupied Holland during the Holocaust. Occasionally you stick your head up and think “hey, I could buy a small country!” or “hey, I’m probably going to be killed soon!” but most of the time you’re like “goddamnit, these potatoes are too salty” or “omg I think he might like me like me.”

That’s what’s deeply wrong, by the way, with this whole #firstworldproblems meme, you know that one? It’s supposedly an excercise in humility and perspective, but in fact it’s an exercise in arrogance. You know, like “my underwear is itchy #firstworldproblems” or “there’s too much goat cheese in my salad #firstworldproblems” or “I can’t get my favorite show on my cell phone #firstworldproblems”. You think people in Bangladesh don’t complain if their underwear is itchy? You think people in the dystopian industrial sprawl of China don’t bitch about their cell phones? There are 1.2 billion cell phones in China, four times as many as there are in the US, 89 per 100 citizens (in the US it’s 103 per 100 citizens). I just read the graphic novel of Waltz with Bashir — there’s this scene where there’s a firefight on the beach in Beruit, and the locals are coming out onto the balconies of their highrise beachside condo apartments to watch the gunfight like it’s a movie, leaning on their railings, smoking and kibitzing. Humans can get used to anything. Our focus is local. I grew up during the crack and AIDS epidemics, with most experts telling us that global nuclear annihilation was immanent, and I knew all that, but still I was mainly interested in playing D&D and going to 7-11, right? So it seems very clear to me that if there’s a zombie apocalypse, a lot of people are going to feel like that’s security’s job to deal with, and they need to get the next feature out. I mean we are currently dealing with the longest-running war in U.S. history, the irreversible melting of the polar ice caps, antibiotic resistant tuberculosis, and looming government financial default, but we’re still mainly interested in watching videos of cats. Why would zombies change anything?

I went back and looked at an early draft of the story — this dynamic, the foregrounded mundane and the offstage carnage, was in it from the beginning. Mostly what changed in revisions were plot and structure things. The story has a better ending now; it just kind of trailed off in earlier drafts.

Michael Noll

Zombie stories and other monster stories, especially vampire stories, are everywhere you look right now–and have been for a few years. They’re scary and thrilling, of course, but I wonder if their appeal runs deeper than just thrills and goosebumps. More than a few people have pointed out that zombies and vampires tend to reflect our fears as a culture (fear of outsiders, certain kinds of sexuality, fear of death). But I wonder, given the present wars and political violence, if monster stories don’t somehow put mass violence at a remove–in other words, putting our fear of such violence into a form that we can consume without being overwhelmed with fear or terror or grief. What do you think? What’s the power or appeal of zombies?

Benjamin Rosenbaum

I think this is a very good insight. It’s certainly one main job of the fantastic, in general, to put things at a remove where we can deal with them. When we think directly about dangers that really exist, we can get caught up in despair or anxiety, and sink. Adding an element of the impossible is one way of freeing up our minds, so that we relate to the danger with playful creativity. Often, this kind of distancing can make the emotional impact of a story greater. We’re less likely to get overwhelmed and shut down if there’s a balance between the absurd or imaginative and the horrific.

There are other techniques that can do this in realistic narratives. I recently read Ishmael Beah’s A Long Way Gone, his memoir of being a child soldier in Sierra Leone. What happened in his life was, he had this relatively idyllic, calm, rural childhood, and then the war came and first he was fleeing and starving as a refugee, and then he was brutalized and drugged and forced to murder people, and then he got out and was rehabilitated. If he told it in strict chronological order, it would start out pleasant and slow, and then descend into just unbearable awfulness, and then level out into a long and difficult and slow, if hopeful, recovery. That would be really hard for the reader to take. When you got to the part with twelve-year olds killing and mutilating people, you wouldn’t be able to go on without checking out emotionally. So what he does is very sophisticated and wise. He starts out chronologically, but as it gets worse — in the part where they are wandering around starving and being chased away from villages and seeing people die — he salts it with flashbacks. You’ll be in some truly horrific scene and he’ll say “oh, and this reminds me of the story my uncle used to tell back in the village” and he’ll give you something whimsical or sweet. And it’s not cheap or gimmicky, because he’s not just doing it to protect you from being overwhelmed. He’s also honoring the village that was lost, he’s sharing with you the whole reality of where he came from, which is not just the horror of the civil war but also the humane, pleasant ordinariness of the lives it intruded into. He’s showing you that Sierra Leone is not just child soldiers killing people, but also uncles telling stories at dinner. And when he gets to the worst part — where he actually becomes a soldier — he gives us very little of it, before skipping ahead to the story of rehabilitation, and then gradually feeds us the horror in small flashbacks, interleaved with things getting better. The treatment of chronology is very deft. He’s protecting the reader, not in order to insulate the reader from what happened so that the reader doesn’t care, but rather so that the reader will care — so that we won’t get overwhelmed and start reading it as just a story of terrible people in some terrible place. He’s resisting being sensationalized, resisting the role of the victim, insisting on constantly putting forward his own and his people’s humanity and agency and ordinariness.

So that’s one thing. Fantastic elements can serve the same kind of purpose, of distancing us enough so we can connect.

Mass violence is one thing zombies can stand for. Pandemics are another — this is definitely a zombie story in the spirit of 28 Days Later, where it’s a grittily real medical catastrophe that’s going on. A related thing that interests me about zombies is that they’re about dehumanization. Someone is infected with something that makes them dangerous and violent — do you see them as a monster, or as a person with an illness? There’s a way in which the apocalypse is often used to grant the characters, and the readers, license to escape a world in which we’re expected to deal responsibly with other people, to tolerate difference, to resolve conflicting needs; if everything falls apart enough, we have permission to just chop off the heads of people who we find difficult. Zombie stories are also about isolation. When I moved to Switzerland the most recent time, and was feeling very disconnected, I found myself having obsessive daydreams about pandemic flu clearing the streets, about having to subsist on what was in my apartment, to bar my door.

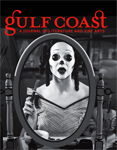

Monsterhearts is a roleplaying game where players explore the confusion that comes both from growing up and feeling like a monster.

Monsters can stand for a lot of things. There’s a really brilliant tabletop roleplaying game, probably the best-designed roleplaying game I’ve ever played, called Monsterhearts, about the messy lives of teenaged monsters. One thing that’s amazing about it is how the game explicitly instructs you to create fiction that operates on both literal and metaphorical levels, simultaneously. Your Werewolf feels out of control of his body, which is changing without his consent — like every teenager’s, but also like a werewolf. Your Ghost feels invisible and lost, trapped by the past and like no one can even see, much less understand her, plus she actually can walk through walls. Your Vampire is about temptation and emotional manipulation and dangerous desire and also bites people. The game captures the balance that fantastic fiction strikes at it best — the fantastic elements evoke emotionally real things without being reducible to them. It’s not allegory, it’s symbol, which means it doesn’t collapse into a hidden meaning like a code, rather it radiates out meanings, generating echoes of echoes.

December 2013

Michael Noll is the editor of Read to Write Stories.

Tags: Benjamin Rosenbaum, how to write a short story, Kelly Link, Lauren Myracle ttyl, M.T. Anderson Feed, Monsterhearts, short stories, tor.com, Zombies