Christopher DeWan is the author of Hoopty Time Machines, which Aimee Bender called “funny, hooterharp, playful zingers of stories that reach right out to grab a reader.”

Christopher DeWan is a writer and teacher living on Los Angeles. He’s the author of the flash fiction collection Hoopty Time Machines and has published over fifty stories in in journals including Hobart, Juked, Necessary Fiction, Passages North, and wigleaf, and he has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize. He has had TV projects with the Chernin Group and Indomitable Entertainment and has collaborated on transmedia properties for Bad Robot, Paramount, Universal, and the Walt Disney Company. His screenwriting has been recognized by CineStory, Final Draft, the PAGE Awards, and Slamdance, and he is recipient of a fellowship from the International Screenwriters’ Association (ISA). He is currently chair of creative writing at the California State Summer School for the Arts.

To read an exercise on using emotion to make readers care about a story’s big-conceit elements, inspired by DeWan’s story “Voodoo,” click here.

In this interview, DeWan discusses the ways that second-person POV and first-person video games are similar, the pleasure of unknowing in flash fiction, and the emotional punch in works by Aimee Bender and Kevin Brockmeier.

Michael Noll

“Voodoo” is written in second person, which is one of those things that often happens without thinking at the beginning of a draft. But at a certain point, you must decide whether to stick with it or use reliable old third or first person. For this story, what made second person the right POV?

Christopher DeWan

I have a theory about second-person—wholly untested—that it works best for stories that are inherently about identity. There’s an effect that happens when I read a second-person story that reminds me a little of playing a first-person videogame, a sort of amnesiac effect where, in the game, I’m supposed to *be* this person but I also know almost nothing about this person: I stumble cluelessly through “my” home trying to collect information to understand who I am. Second-person fiction reads like that to me: the story is a series of puzzle pieces for readers as we actively participate in assembling the identity of the narrator.

In this story, “Voodoo,” the narrator feels alienated and confused by his daughter and, at some level, his whole life: he’s assembled all the trappings of a normal adult, but he doesn’t feel like one. His daughter and her room and his house and his wife should all feel very familiar to him, but they don’t—and I like the way second-person helps convey this alienation. Second-person blindfolds the reader, spins them around, and makes them feel a little lost.

Michael Noll

The story’s opening suggests, broadly speaking, a couple of possibilities: the daughter has made voodoo dolls and is using them to harm her parents or it’s all in her father’s head. The story never chooses one over the other. It also doesn’t escalate the premise into a plot that would require a much longer story, something that seems like it would destroy the great uncertainty that you’ve created. Were you ever tempted to enlarge this story, or did you always know it would hang in this particular moment?

Christopher DeWan

You’ve given away the secret of the entire book: a collection of forty-five short stories so short that I never have to decide anything!

This is one of things I love about flash fiction: the form allows me to write a story about the moment before a story, take it right up to the point that something catastrophic will have to happen—and then the story’s over. The reader is just left there in that moment, teetering on the cliff’s edge, imagining all the things that might happen next. For me, that not-knowing is a more interesting place than the knowing.

But there are many stories in this collection I could imagine enlarging. The book is basically forty-five inciting incidents for forty-five future novels. Now I’m just waiting for a forty-five book deal.

Michael Noll

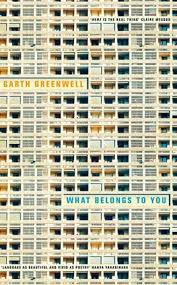

Christopher DeWan’s story “Voodoo” is included in his new collection of flash fiction, Hoopty Time Machines.

The book, Hoopty Time Machines is subtitled, “Fairy Tales for Grownups,” which gets at one of the weird things about fairy tales. The originals from Northern Europe were quite scary and told by adults–maybe to kids, often to each other. The death and other horrors in them reflected the very real dangers that people feared. Then, of course, they got sanitized. In this book, there isn’t much death, but there are a lot of unsettling situations: a changeling child, parents who seem to have been replaced by trolls. What is it about fairy tales that seems to convey the feelings we get from real life?

Christopher DeWan

There are a lot of people who study fairy tales as a genre and I should say I’m not one of those people: I’m no fairy tale scholar. But I am a big fan, and particularly a fan of a fairy tale’s ability to evoke deep, resonant, inexplicable horror: “Why did he grab himself by the foot and tear himself in half?!?” etc.

What I’m hoping to do with this book is explore some of the lingering cobwebby corners of adult psychology that still resonate within those murky kid fears. There are plenty of things in our lives that don’t make sense, exactly, but we push them out of focus so we can function as adults in the world. They’re still in there, lurking, making a mess of our minds in ways we don’t fully understand.

Michael Noll

Your book is blurbed by Aimee Bender and Kevin Brockmeier, in whose footsteps it obviously walks, as do so many books. They, along with a few other people, basically created the genre of American fabulism and fairy-tale-inspired fiction. And, of course, they were drawing upon the work of writers like Angela Carter and Donald Barthelme. Was there a particular story that made you think, “Yes, this is the kind of writing I want to do?”

Christopher DeWan

Well, first, I can’t overstate how much I admire both of them—actually, all four of those writers you mention. I first read Aimee Bender around the time her first book came out, and I consumed that book in a single sitting, and I remember being dazzled and awestruck and most of all I remember feeling a great sense of liberation, like, “It’s okay to do that?!” I was always into fabulism—I mean, we all are when we’re kids, but I just never outgrew it. So Angela Carter and Donald Barthelme and then Aimee Bender helped me form a very permissive view of what literature can be, helped reinforce in me this idea that I think I held intrinsically: that strange, magical stories have value to adults, too.

But honestly, the thing I admire most about Aimee Bender and Kevin Brockmeier has very little to do with fabulism and has much more to do with the enormous compassion and empathy they bring to the characters in their stories. Brockmeier’s The Truth About Celia is one of the most beautiful books I know, and I think the only reason it tips into fabulism is because the events in the book are too horrible for a person to reckon without inventing some fables to help mediate the horribleness.

I love these two writers. What gigantic, wonderful, fair hearts they both have. I learn so much from how both of them see the world—and yes, absolutely, that’s the kind of writing I want to do, too.

October 2016