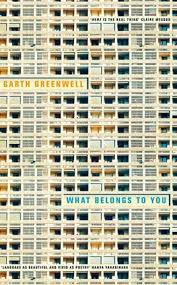

Garth Greenwell’s novel What Belongs to You tells the story of a young American man teaching in Bulgaria and his complicated relationship with Mitko, whom he meets in a public restroom.

When I was an undergrad, one of my writing teachers lamented that too many novelists were trying to write books that could easily be filmed. A good novel, she said, moved differently than film; it created a kind of narrative space that could not be captured on a screen. And what filled that space? Human thought.

This isn’t the only view of what constitutes good writing, and it’s probably not even a majority opinion, but it does suggest an interesting question. If a scene that can be filmed—i.e. one with dialogue and action and subtext to inform both—is not the only approach to a scene, then what else is there?

One answer can be found in Garth Greenwell’s new novel What Belongs to You. You can read a long excerpt from the beginning of the novel here.

How the Story Works

In his review of What Belongs to You in The New Yorker, James Wood writes this:

The novel contains no direct dialogue, only reported speech; scenes are remembered by the narrator, not invented by an omniscient author, which means that the writing doesn’t have to involve itself in those feats of startup mimesis that form the grammar, and gamble, of most novels. In an age of the sentence fetish, Greenwell thinks and writes, as Woolf or Sebald do, in larger units of comprehension; so consummate is the pacing and control, it seems as if he understands this section to be a single long sentence.

Wood’s “feats of startup mimesis” are another version of “can be filmed,” or at least “can be filmed in the way we’re accustomed to seeing on-screen.” In place of these feats, he claims, Greenwell inserts “larger units of comprehension.” That’s all a bit vague without an example, and so here is a brief passage (only a small part of a longer paragraph) from What Belongs to You. A bit of setup: the novel’s narrator is a young American man teaching in Bulgaria. In this scene, he’s in the National Palace of Culture, in the restrooms,which are frequented by gay men because they “are well enough hidden and have such a reputation that they’re hardly used for anything else.” The narrator encounters a man there, and that encounter, brief in terms of actual minutes, occupies almost ten pages. Here is why:

I wanted him to stay, even though over the course of our conversation, which moved in such fits and starts and which couldn’t have lasted more than five or ten minutes, it had become difficult to imagine the desire I increasingly felt for him having any prospect of satisfaction. For all his friendliness, as we spoke he had seemed in some mysterious way to withdraw from me; the longer we avoided any erotic proposal the more finally he seemed unattainable, not so much because he was beautiful, although I found him beautiful, as for some still more forbidding quality, a kind of bodily sureness or ease that suggested freedom from doubts and self-gnawing, from any squeamishness about existence. He had about him a sense simply of accepting his right to a measure of the world’s beneficence, even as so clearly it had been withheld him.

The first sentence is pretty straightforward: The narrator desires the man but doubts he will get any such satisfaction.

The second sentence starts in a similarly clear way (“For all his friendliness”) but instead of sticking to what is clear and evident, the narrator begins to suss out what lies behind that friendliness. He identifies it as a “more forbidding quality, a kind of bodily sureness or ease that suggested freedom from doubts and self-gnawing, from any squeamishness about existence.” Earlier, the man has been described in specific detail, but this sense of him is particular to the narrator. Someone else might see nothing like this at all. In short, the prose has jumped from what is to what seems to be to the narrator. The world and the people in it are being viewed, thickly, through the narrator’s consciousness. The final sentence extends this filter and the sense of being that it reveals: “a sense simply of accepting his right to a measure of the world’s beneficence.”

Of course, that filter is present in all novels. In first-person narration, the narrator provides the filter. Everything we see is seen through the narrator’s eyes. In third-person prose (and, really, in all novels), the filter is the author’s. And yet we forget this because most novels work hard to make us forget; they want us to see the world of the novel as clearly as an image in a film.

A review in The New York Times by Aaron Hamburger calls the style used by Greenwell “an ‘all over’ prose style, similar to that of a Jackson Pollock abstract expressionist painting, in which all compositional details seem to be given equal weight,” comparing it to the prose of Ben Lerner’s novels. But that doesn’t seem quite right. Greenwell’s narrator isn’t scattered. He’s pretty focused on the man in front of him and his desire for him, and it’s that focus—the act of seeing and thinking about—that becomes the essential material of the novel.

Lerner does something similar. Here’s a passage from his most recent novel, 10:04, after the narrator has had sex:

I was alarmed by the thoroughness of what I experienced as Alena’s dissimulation, felt almost gaslighted, as if our encounter on the apartment floor had never happened. Here I was, still flush from our coition, my senses and the city vibrating at one frequency, wanting nothing so much as to possess and be possessed by her again, while she looked at me with a detachment so total I felt as if I were the jealous ex she’d wanted to avoid, a bourgeois prude incapable of conceiving of the erotic outside the lexicon of property.

As in Greenwell’s novel, Lerner’s prose is interested in sense and what an awareness of the world feels like: “what I experienced as Alena’s dissimulation, felt almost gaslighted.”

Of course, these are two very different books with very different narrators. Lerner’s narrator spends a lot of time on social media, and so his consciousness actually is scattered at times because it is pinging along with the rapid delivery of information from Facebook and Twitter. He’s also a poet, and so he’s apt to fall into long interior discourses about art and poetics. In other words, the things he thinks about are different, but the general style of the narrator, its general focus on consciousness, is similar.

Of course, any time reviewers start comparing the book at hand to some deceased writer’s work (Wood chooses Woolf and Sebald) or to writers with highly distinctive styles (Hamburger in The New York Times chooses Lerner and Karl Ove Knausgaard), you know that the book is doing something so new that it isn’t easily classifiable. Yet, let me take my own shot: In its focus on a mind actively thinking about the experience it is having, Greenwell’s (and Lerner’s) work resembles the prose of Henry James, particularly The Beast in the Jungle.

That book, like Greenwell’s, begins with a charged encounter, a man and a woman at a party. The woman tells the man they’ve met before and asks if he’s forgotten. Here is what comes next:

He had forgotten, and was even more surprised than ashamed. But the great thing was that he saw in this no vulgar reminder of any “sweet” speech. The vanity of women had long memories, but she was making no claim on him of a compliment or a mistake. With another woman, a totally different one, he might have feared the recall possibly even some imbecile “offer.” So, in having to say that he had indeed forgotten, he was conscious rather of a loss than of a gain; he already saw an interest in the matter of her mention.

Much about James’ novel is different from What Belongs to You. It’s about inaction, and Greenwell’s isn’t. There is dialogue, and Greenwell writes almost none. Yet to quote Wood, both novelists are interested in “larger units of comprehension,” and those units are filled with character’s sense of what is happening around them.

The Writing Exercise

Let’s describe a character’s sense of an interaction, using What Belongs to You by Garth Greenwell as a model:

- Choose who will have the interaction. The possibilities, of course, are endless. It can be between lovers, siblings, parents, coworkers, friends, business associates, or enemies, or it can be transactional, like the interaction between store clerk and customer.

- Choose which perspective will serve as the filter. In other words, whose eyes are we seeing the scene through? This can work in third-person as well as first-person, as Henry James makes clear in The Beast in the Jungle.

- State the desire. Despite the capacious units of comprehension that Greenwell creates for his narrator’s consciousness, certain things are quite clear. Number one would be the narrator’s desire. He wants the man in the restroom. Without that clear desire, the passage that follows might come untethered from the experience it is pondering. The reader needs a reason to wonder what the narrator thinks, and that reason is the possibility that the narrator might get, or not get, what he wants. So, state as clearly as you can what the character wants out of the interaction: money, love, some object, acceptance, permission, refusal, rejection, a chance to fight, a chance to make up, or even a mindless conversation. If no one wants anything in the scene, it’s probably not worth writing. Don’t be subtle. Greenwell’s narrator thinks, “I wanted him to stay.” Be just as direct.

- Describe the surface. Greenwell does this elsewhere in the scene and refers to it with the phrase “For all his friendliness.” How does the interaction seem at first glance. If the other character is putting on an act, what is the act? What is intended to be seen?

- Peer behind the surface. Greenwell’s narrator finishes the sentence that begins “For all his friendliness” by looking closer and thinking about what lies behind that friendliness. It might be useful to use Greenwell’s actual syntax as a model: “more forbidding quality.” So, you could write a sentence like this: For all his/her ______, there was a more _____ quality.”

- Let the character draw conclusions from this sense of things. Once the narrator/character determines that something does, in fact, lie behind the surface, let the character think about it. The desired end of thought is, usually, conclusion, which is what Greenwell’s narrator reaches: “He had about him a sense simply of…” Again, try using that syntax: He/she had about him/her a sense simply of _____.”

The goal is to expand the room your prose offers to its characters consciousness, the narrator’s sense of what is happening. You can make that room an efficiency or a mansion. Either way, the idea is to add a character’s sense of things, something that can be described in prose but not easily portrayed in film.

Good luck.