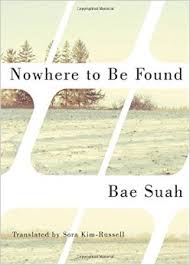

Nowhere to Be Found by Bae Suah tells the story of a young woman trying to make sense of her life and world in South Korea.

Some stories are about individuals, and the drama between them is so intense that the backdrop could be the Death Star or a blank wall and it wouldn’t matter. In other stories, the backdrop matters. Take it away, and the story vanishes. Whether the story is about a society as a whole or a particular town or neighborhood, the challenge is to establish the backdrop as quickly as you’d establish a character. This is, of course, not easy.

One story that shows how it can be done is Bae Suah’s novella Nowhere to Be Found. It was originally published in 1998 in Korean and was recently translated into English by Sora Kim-Russell and published in the United States. You can read the opening pages here.

How the Novella Works

Here is how the novella begins:

In 1988 I was temping at a university in Gyeonggi Province.

Mostly what I did there was send lecture requests to part-time instructors, make adjustments to their class schedules, mail them their paystubs, and field complaints from students. As far as the work went, I didn’t have any major complaints of my own. It was the kind of clerical work that anyone could have done without any special qualifications or expertise.

Many readers will likely be familiar with the tedium of such work and also the way it was done:

At this job we could chew gum or do our nails while answering the phones and take over two hours to type even the sparest syllabus. We weren’t lazy or indifferent or anything. It was just the nature of the work…I didn’t have too many tasks, but I also wasn’t so idle that I could have passed the time knitting. When I was working, the hours went by at what I can only call a measured pace.

Another writer might have dug into the absurdities that are intrinsic in such work, but Bae has something different in mind:

We got a month off while classes were out of session. I spent that month working part-time in a dye factory close to my house. My job was to screw caps onto tubes of dye using a mechanical device. That was a long time ago. I’m sure that dye factory has since found a more modern solution to that primitive final step of production. But then again, if they had modernized any earlier, I wouldn’t have spent that summer wrapped in the suffocating smell of acrylics.

Bae is up to something larger than the story of a single person stuck in a soul-killing job. The novella’s target is 1980s-era South Korean society as a whole, and, as you might expect given the nature of the work, there is some large, inhuman imagery:

“That’s how things get done, just as the less delicate components of a machine submit to the will of the machine without any conscious thought or shred of volition while being ground down.”

What makes this novella bold and interesting is that it finds perverse ways of bringing the machinery of society to bear on the components. Here is a great example from early on:

Even now I think maybe my family is just a random collection of people I knew long ago and will never happen upon again, and people I don’t know yet but will meet by chance one day.

These are recurrent themes in the novella: larger, impersonal forces and disconnection. They’re powerful and interesting, and yet they have the potential to lose their power as soon as the reader becomes used to them. And so Bae introduces the novella’s first dialogue, between the narrator and a “guest lecturer on criminal sociology”:

“This week’s topic is murder.”

“Oh.”

When I was an undergrad, one of my literature professors made fun of 1920s political poetry, with its predictable imagery of downtrodden masses and greedy capitalists. This novella is different because it so often jolts the readers out of their expectations—causing them to lean forward to really pay attention and setting them up to be smacked down by the societal machinery all over again. Nowhere to Be Found manages to replay that cycle—beat-down, jolt, beat-down, jolt—for 100 pages. It’s an impressive feat.

The Writing Exercise

Let’s try writing about society (without becoming predictable) using Nowhere to Be Found by Bae Suah as a model:

- Create a machine for the society. Another way to put this is this: Create a metaphor. In Nowhere to Be Found, the jobs are clearly representative of the society as a whole. The jobs are noteworthy because of how they reveal the mechanics of the society. While you can create a metaphor by thinking, “I’m going to create a metaphor now,” you can also approach the task from another angle. Try finishing this sentence, “When I think about (the place), I immediately think of _____.” Trust your imagination to fill in the blank with a job or hobby or whatever. Don’t worry about if it’s a good metaphor. If it’s an essential part of the place—not to everyone but to you—it will eventually take on the role of a metaphor.

- Acknowledge the machinery. In other words, give the narrator or characters some awareness of the situation. (Without that awareness, you risk writing a morality play.) There are different levels of acknowledgment. The highest level requires a statement like this: “The whole society was about _____.” While this is possible (Bae writes sentences like this), it’s also difficult to pull off. It’s often more manageable to let the characters think practically about their immediate surroundings, as the narrator does in this sentence: “It was just the nature of the work…” Try using that word, nature. Let the character ponder or make a statement about the nature of whatever surrounds her. You may find yourself working up the scale to the nature of the society as a whole. Or, you won’t. Stop when the writing begins to crumble under its own weight.

- Give the characters agency. Part of the reason that Albert Camus’ The Stranger is so powerful is that the narrator acts. He chooses to do things. The motive behind those actions isn’t always clear, but the action is dramatic. This is an important lesson to remember: even if characters are just floating along, they need to occasionally act as if they have some control over themselves. (In The Stranger, the narrator chooses to help set up his friend’s girlfriend for a cruel joke.) In Nowhere to Be Found, some of the moments of highest tension occur when the narrator behaves in ways that grind against the machinery she’s caught in. A good rule of thumb is this: When a scene feels like it’s about to end on a down note, keep writing. What if the character suddenly pushed back and refused to accept that down note? What would happen then?

- Reveal the machine at work in a surprising way. Machinery tends to work on several levels: the obvious one and the less obvious one. In Bae’s novella, the machinery is the economics of South Korea: the way that low-paid, tedious work turns people into laborers and into automatons. In other words, the machine is exterior to people. What’s surprising is when Bae makes the machinery interior as well, as in the passage about family members seeming like random people. Don’t create an impermeable wall between a character’s interior and exterior. How can her thoughts or actions reveal the presence of the forces she tries to resist?

- Throw a wrench into machine. Make the readers believe that the machine can be broken or that it’s possible to step outside of it for a period. Again, there are obvious and less obvious ways to do this. There’s the V for Vendetta method: bomb Parliament. Then, there’s the Nowhere to Be Found method: introduce a wild card: “This week’s topic is murder.” These wild cards don’t need to become part of the plot, they only need to throw askew the reader’s expectations. No society is totally flat. Every place contains pockets of unexpected absurdity or evil or goodness. Create those pockets in your story. How can you introduce a character, even momentarily, who is working not against the system but on a different plane altogether? He or she may still be part of it, but the level of acknowledgement or the choices he makes are different and upend our perhaps simplified ideas of the place.

Good luck.

![Ru Freeman's novel On Sal Mal Lane "soars [with] its sensory beauty, language and humor," according to a New York Times review.](https://readtowritestories.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/9781555976422.png?w=490)