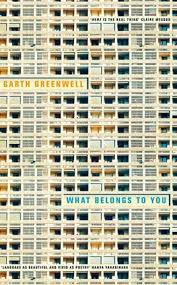

Daniel Oppenheimer’s book Exit Right has received rapturous reviews, like this one from the Washington Post: “This book proves so satisfying precisely because it leaves you wanting much more.”

Daniel Oppenheimer’s articles and videos have been featured in The New York Times, The Atlantic, Tablet Magazine, and Salon.com. He earned a BA in religious studies from Yale and an MFA in nonfiction writing from Columbia. He lives in Austin with his wife, the historian and psychotherapist Jessica Grogan, and his kids Jolie and Asa. He is Director of Strategic Communications for the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement at the University of Texas at Austin. Exit Right: The People Who Left the Left and Reshaped the American Century is his first book.

To read an exercise about revealing tension indirectly, inspired by Exit Right, click here.

In this interview, Oppenheimer discusses quoting versus paraphrasing, the most under-recognized tool in the nonfiction writer’s trade, and the most insightful comparison of Donald Trump and Ted Cruz I’ve seen yet.

Michael Noll

I love the passage about Whittaker Chambers’ parents, the way they used everything in the world as a proxy battle for their mutual dislike of each other: the house that Chambers’ father allowed to go into disrepair, the way they treated their kids. You quote Chambers on this subject, but you also write about it in your own words. How did you know what to quote and what to summarize, what to footnote and what to pass by un-noted?

Daniel Oppenheimer

When it comes to quoting vs. paraphrasing or characterizing, I’m always trying to balance a few considerations. I like quoting, and particularly with someone like Whittaker Chambers, who was such an evocative writer, there’s great value in quoting him directly. He gives a good quote.

At the same time I think readers, for whatever reason, tend to zone out and begin to skim if you quote at too great length. I don’t usually love it, as a reader, when I encounter too many or too lengthy quotations. It feels like the writer fell too much in love with the material and lost sight of the reader—maybe also like they’re wanting the quotes to do their work for them. There are exceptions to that generalization. I think of someone like Janet Malcolm, who will quote from her interviews for pages, or of WG Sebald, who will also quote for pages. I’ll follow them anywhere, including into incredibly long quotations.

But they’re brilliant, and there’s also something about what they’re trying to do, as writers, that’s well served by their techniques. Malcolm is fascinated by the stories people tell about themselves, and so it makes sense that she shows that process at length. Sebald is trying to blur boundaries between himself and others, and the present and the past, so it serves that end for him, particularly since (if memory serves) he usually doesn’t even use quotation marks to signal that he’s begun quoting. It all kind of blends together.

I haven’t yet hit upon a method that feels organic that allows me to quote at great length, so I treat quotations in a more conventional way, and in general try to be somewhat sparing. In practice, I tend to include more quotes in the early drafts and then pare away as I revise, leaving only the ones that really work and seem really necessary in terms of giving a flavor of who the person was and how they saw the world.

I also like summarizing, paraphrasing, and distilling for their own sakes. Or at least I like having done it well. Some of my best writing happens, I think, when I’m trying to sum up what someone else thinks or has said. I’m trying to inhabit them, and at the same time to overlay in a subtle way the additional perspective that I bring to their story. In truth it can be a pretty sneaky thing to do, when I pull it off. I make it seem like I’m just paraphrasing or summarizing, but I’m actually inflecting the readers’ interpretation of what’s going on in a rather manipulative way.

In terms of footnoting, it’s less complex. I’m not an academic, so I don’t feel the need to footnote everything or list every source. I needed to do some of it for a few reasons: to legitimize myself, to serve that academic purpose at a basic level, and also to occasionally draw attention to other books or articles or writing that deserve to be read. I also, like a lot of writers, use the footnotes as a basin of last resort for passages that it made sense to cut from the main text, for reasons of flow and space, but that feel too good to just get rid of entirely.

Michael Noll

Many of the reviews (New Yorker, Atlantic, New Republic, Washington Post, Barnes & Noble) of the book have noted its terrific prose, and I agree. For example, you write this about the 1920s: “Any kind of sickness—an infected hangnail, a fever, a cough—might be the first domino in a short cascade that led to death. Epidemics and pandemics rolled across the populace like stampedes. Fires took out cities.” This is such vivid language, active and compelling for what is essentially a passage with a mechanical role: give the reader a sense for Chambers’ world. What was your process for writing the book? Did you research and take notes and then write? Or did you write as you researched? I guess I’m wondering at the head space that passages like this one came out of.

Daniel Oppenheimer

I’m glad you like that passage. I’m happy with myself every time I read it. My wife will laugh when she sees you quoting that, and will probably make an obscene joke about how happy it must have made me.

Daniel Oppenheimer’s political biography, Exit Right, tells the story of six men who converted from the American left to American Conservatism—with an eye toward what the history and experience that set the stage for their conversions.

I think I have a few other passages in the book that do that same kind of thing, distilling a lot of historical or social background into a few tight, evocative paragraphs, and I’m excessively proud of them. This kind of distillation has to be among the most under-recognized and under-theorized tools of the nonfiction writer’s trade. There should be entire craft classes on how to do this, because you need that background in a lot of historical and journalistic writing, and yet it’s so tempting to do it in a half-assed way, to knock it out in workman-like prose so you can get back to the sexy stuff. And I get it. It’s hard work, and when you do it well it’s pretty self-effacing. You’ll rarely be recognized for doing it well (unless you get interviewed by Michael Noll, apparently). But it’s so important. And if you do it poorly, it just slows the narrative down so much.

In answer to your specific questions, I started out the book doing a whole bunch of research before I began writing. That was a good way to go, in terms of writing passages like that one, but it was a bad way to go in terms of finishing the book in anywhere near a reasonable amount of time. So for Hitchens (which I wrote first even though it’s the last chapter chronologically), Chambers, and Burnham, I did it that way. Then I realized I needed to speed up if I was ever going to finish the book, so with Reagan, Podhoretz, and Horowitz it was more the latter strategy, researching and writing at the same time. I’d do a bit of reading in advance, usually the main biographies and autobiographies, and then I’d begin writing while also delving into the rest of the material (their writings from the time, what their colleagues had to say, other people’s memoirs, etc.). My guess is that these latter three chapters have fewer of the kinds of passages you quoted, which is too bad. At the same time I think they’re lighter and more fluid in some appealing ways. Research can sometimes weigh you down. So I honestly don’t know which strategy worked best for me, purely in terms of the quality of the book.

Michael Noll

You write this about Chambers: “There are different ways of reading the arc of Chambers.” This is probably true about all of the men you profile. About Christopher Hitchens, who abandoned the left several decades after Chambers, you summarize the view of his conversion from the left, from the right, and from his own eyes. These different ways of reading these men can make it difficult to see them with fresh eyes, but you can hardly avoid the filters and spin. How did you find your own way of seeing the men?

Daniel Oppenheimer

I was talking to my brother the other day about why it is that no one has written this book before, about people who’ve gone from the left to the right. In a way it seems like an obvious book to write. My theory, which he liked, and which touches on this question, is that I brought to the project a rare mix of humility and arrogance (or at least confidence).

What’s humble is that I’m just taking what everyone else has already written and said on the subject and synthesizing and summarizing and distilling it. I’m not venturing any great theses about history. I’m not uncovering any new material on these people. I’m not even offering radical new takes on them. Most writers who could pull off something like this have too much ego and ambition to be so self-effacing.

The arrogance is that I trusted that there was something about the way I write, and the way my brain works, that was going to produce writing that felt fresh even though I was going over territory that has been so thoroughly gone over before. A lot of writers, I suspect, would it find it daunting to have to say something new about folks like Whittaker Chambers and Ronald Reagan and Christopher Hitchens, who’ve been written about so many times over so many years. I didn’t worry about it so much. I trusted my voice.

Michael Noll

The book is remarkably understanding of its subjects, several of whom were often not viewed charitably by the people who knew them best. In the introduction, you write, “We can make judgments—we can’t not make judgements—but they should be made with an awareness of how hard it is to be a person in the world, period, and how much more confusing that task can become when you take on responsibility for repairing or redeeming it.” As you researched and thought about these men in this humanizing light, you must have found yourself identifying with them. That is the goal of humanizing people, right? If you did identify with them, could you begin to identify with their political conversions and beliefs? In the words, did the book affect your own political views at all?

Daniel Oppenheimer

I did find myself identifying with these men. In a sense that was the method of the book. Let’s see what it looks like when I try to see as deeply into their stories as possible, through their eyes, and then complement that with the perspective I can bring to their lives as someone who is not them, who can see certain things about them more clearly because I’m not them.

I was writing an essay recently on Donald Trump, whose views I find truly awful, and the more I read about him the more sympathetic I became, to the point where there’s a part of me that kind of wants him to win the Republican nomination, simply because he’s the only one to whom I’ve cathected in that basic way. I watch him up on stage, at the debates, and I feel for him when he loses control. That’s just how my brain works. It would be interesting to do an experiment in which I spent a lot of time researching Ted Cruz just to see if the same thing would happen. I suspect not. I think Cruz is empathy-proof. I think he’s done such a good job of polishing off anything in him that’s vulnerable that there are no visible cracks left. I need the cracks to get access. Donald is almost all cracks.

So does this process of identification influence my politics? Well, yes I’m sure it does, but not in a very linear way, any more than a novelist is likely to be influenced in a linear way by writing with empathy about characters who are evil, or who do evil. The novelist doesn’t become more evil as a result of that, or more likely to do evil. What they become is more able to comprehend why someone might do evil. I’m sure that could lead to more evil, depending on the novelist’s character, but my guess is that it’s more likely to result in the opposite, in a deepening of the empathizer’s humanity and capacity for goodness. I haven’t become more conservative, but I like to think that I’ve become more understanding of why someone might leave the left, and why they might embrace conservatism.

If anything, I’ve probably gotten more ruthless as a leftist. It doesn’t feel as personal anymore. It’s about power, and who wields it, and how to change the balance of power to better achieve the ends I’d like to see achieved. I have empathy for the people on the other side. I don’t think they’re bad people just because they don’t share my political priorities. If I were super rich, for instance, I’d probably persuade myself that my wealth was a manifestation of my virtue, and that a healthy society is one that celebrates the wealthy and recognizes them as the natural leaders of their fellow men and women. I can imagine that. But I think it’s a toxic perspective when it acquires too much influence in the polity, and that that’s the best reason to do what we can to diminish the power and influence of the wealthy. It’s not personal. In fact, in that project making it too personal can obscure the best strategies. I don’t need them to be evil. I just need them to lose.

I read Saul Alinsky not too long ago, and what struck me about him was how pragmatic and non-moralizing he was about what he did. He wanted the world to be a certain way. The other side wanted it to be a different way. Both sides were going to do what they could to win, and he was going to be as clever and rude and tough and sneaky as he could be to increase the odds that his side won. Of course he cared deeply, and could get angry, but he had a real ability to see his political opponents with empathy and detachment, and to imagine the world through their eyes, and that helped him enormously in defeating them.

I’m no Saul Alinsky, but I think I have some of that in me. Honestly, someone should hire me to devise strategies to take down conservative politicians. I think I’d be a brilliant, ruthless, empathetic bastard.

March 2016

Michael Noll is the Editor of Read to Write Stories.

Michael Noll is the Editor of Read to Write Stories.

Tags: Daniel Oppenheimer, empathizing with characters, Exit Right, political writing, quoting versus paraphrasing, writing exercises